For decades we have painted a portrait of designers being the visionaries behind big changes in the way we build things. And while that is true in some part it ignores an important reality: design is part of a system.

Design is not about an individual, but relates to the values of society.

Book Cover of Objects of Desire: Design and Society Since 1750.

This post is based on Adrian Forty’s Objects of Desire , that provides a retrospective insight into design and its impact on society. It is one of the rare design history books that can ground design in its complex social context

The author uses a variety of fascinating examples to show that the way things evolution can’t be considered simply in relation to the increasing technologies and materials available, or as a result of a designer’s creative effort—design encompasses all kinds of social processes and is inseparably linked to the economics of manufacturing, and even politics.

Most importantly, the thread behind a lot of design innovations has been a change in beliefs.

Historically, our vision of life, home, work, and the roles of women and men in society have changed profoundly, and it's important to understand how that impacted design and how that relates to our work as designers.

Design and family values

Drawing room, Rosslyn Tower. (1907)

For example, throughout the late 19th century, beauty was the principal means by which the home was to fulfil its purpose as a place of sanctity. Among its characteristics, beauty included comfort and the satisfaction of the aesthetic senses, but above all it meant the representation of moral virtues of truth and honesty. This leads to a purer application of principles in design, compared to the Victorian era.

Less ornaments, less furniture, and simplicity in color were seeked instead, bound to have a good moral influence upon the members of the household, without anything appearing to be something it was not. For instance, Colonel Eddis had warned of the dangers of "dishonest" design:

“If you are content to teach a lie in your belongings, you can hardly wonder at petty deceipts being practiced in other ways...”

The home of the 20th century followed that of the 19th in certain aspects, such as the physical and emotional separation from the place of work, but with differences in appearance and organization that revealed major changes in underlying values.

The home changed from the function of beauty and spiritual virtue to a source of physical welfare and health. In the twentieth-centure literature about the home, preoccupations about motherhood, children and hygiene replaced instructions about needlework and the Christian virtues.

This leads to the necessity of an aesthetic of cleanliness, which became the norm in the domestic landscape., and induced a redesign of household goods of all kinds. For example, products like the Leonard refrigerator (left) did not convey as well as that of the Coldspot (right) the value of immaculateness.

Left: The Leonard Refrigerator (1929). Right: Sears Roebuck Coldspot Refrigerator (1935). Objects of Desire.

Advertisement for Energine, 1929. Ladies Home Journal, May.

Ultimately, it was advertisers and manufacturers rather than health reformers who must successfully taught the public to worry about hygiene.

Design and industry interests

In this context, the development of electricity was a key element of transformation, but for different causes than we would think of. Since electricity was used mainly for lighting this generated a problem: the demand was limited to the hours of darkness, and the necessary generating capacity remained idle for a large part of the day.

This need to build domestic load, in combination with the desire for higher standards of home sanitation led to the design of new products that reflected this vision of electricity as bright, clean and efficient:

Electrical Development Association poster. (1927)

“Of all the gifts that electricity brings, almost the greatest is the relief from the burden of mechanical, monotonous, everlasting toil, [...] so that the labor involved in cleaning, in heating, in cooking, in washing and other domestic tasks will be performed smoothly by an electrical deputy.

”

Advertisement for electricity. (1980). Company, August 1980.

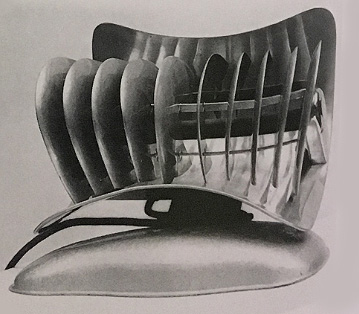

Far from living up to the vision of electricity as a modern source of energy, the majority of appliances on the market in the 1920s looked ramshackle and clumsy. The challenge was to represent some of the qualities of modernity and efficiency in the design of appliances themselves.

“How are we to create this demand for electric heaters? First we must improve their design until they impress by their very appearance—they must simbolize electricity.”

Though electricity is invisible, and no more good, the properties ascribed to it were that it was clean, silent, instantaneous, modern and revolutionary. To symbolize those qualities designers used aesthetics based on the Modern Movement, giving objects like an electric fire a huge change in appearance.

Differentiation by Design

As has happened for centuries in the linkage between art and church to represent power and divinity, design has been employed often as a communicator of hierarchy and expected behavior. It is a topic we may disregard because we get used to it, but the book gives some interesting examples of how design can reinforce class, age and gender roles.

Depending on how society perceived the role of the user, a clear differentiation was made.

Cotton print design patterns designed for the working-class market, English. (1850)

There are examples of cotton print patterns known to have been produced specifically for the working-class market (such as the floral cotton fabric of the image above), while middle-class women wished to be dressed in patterns that they could be sure had not yet been reproduced on cheaper fabrics worn by working class women. When it happened, it even caused the owners of the first, expensive printing pattern to discard them and buy new ones.

Ladies' hairbrushes and men's hairbrushes. Army and Navy Stores catalogue. (1908)

Gender is also made obvious. Although it is unlikely that there was any significant difference between the mode of brushing practised by American men and women the ladies' hairbrushes are distinguished by having handles, and, for the most part, a greater amount of decoration on the backs. The same happens with products like the Philips electric razor, where the lady's razor is coloured and decorated with a floral device, so appearing more delicate and "feminine" that the plain black model for men.

Philips man's electric razor, and Philips "Ladyshave" woman's electric razor. (1980)

These ideas were also noticeable in the office, where organisations maintained a desire to protect hierarchies while giving an illusion of equality and uniformity, and where the role of women at work was still very limited, (thank god these type of ads are less common now as we move forward!). This could be seen represented in the way products were sold, and the visual language imbued into the design of the products. Therefore, objects had a direct relationship with what we wanted to portray as a society.

Office furniture ad. Robin Day. (1965)

In sum, despite the existence of capital, materials, and technology, it is ideas in society what have promoted change in design, for better and for worse.

Because designers generally talk and write only about what they do themselves, design has come to be regarded as belonging entirely to their realm, and the tools and technology they had available at the time, but it is also the interest of the industry and manufacturers what has reinforced ideas in society or given power to new ones.

This is why it would help to think more in terms of what design does, rather than who did it, when looking at the past and analyzing the present. The case was just as usual a century ago as it is today, when manufacturers not designers (even those famous designers we study in Art History) decided which design most satisfactorily communicated the ideas necessary to the product's success.

Perhaps the interesting part is standing in the midst of this complexity, acknowledging the external constraints beyond our creative capacity. It is acting as translators, and balancing the requirements of the market with the ideas we represent in our designs.

Understanding this position, that in a lot of cases we are not the ones making the final decision and there is always a lot of emphasis in increasing economic value to the manufacturer, we are also given a space to act. A space where we can reflect on our own values and ways of seeing life, and materialize them in a physical form. To represent them in a product that will not only add value to the market (which is one of the main reasons why they look for our service) but actually make a point to its customers; add something into their lives.

Ideas give way to design, but design as well can give shape to ideas. Since ideas are intangible, the physical world is what reinforces us their very existence.

So think about a project you are working on right now: what values are being communicated? Are you comfortable with these ideas or do they go against your own beliefs? How do they relate to national or global beliefs or struggles?

And how do we respond to that as designers, and create objects, spaces and services that truly dignify our lives?

References

(1) Forty, A. (1986) Objects of Desire: Design and Society Since 1750. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.