First of all, I'd like to say that I feel really grateful for the education I have received in architecture school and that I've had many wonderful teachers. Nevertheless, it's good to question how we do things, and it is in part what this space is all about. I've been discussing this topic for a long time with friends and colleagues from different countries, and there are issues that repeat in our experiences.

A survey by UK magazine The Architects' Journal reports a shocking statistic: 26 percent of architecture students had received medical help for mental health problems resulting from their course, while a further 26 percent feared they would need to seek help in the future. [1]

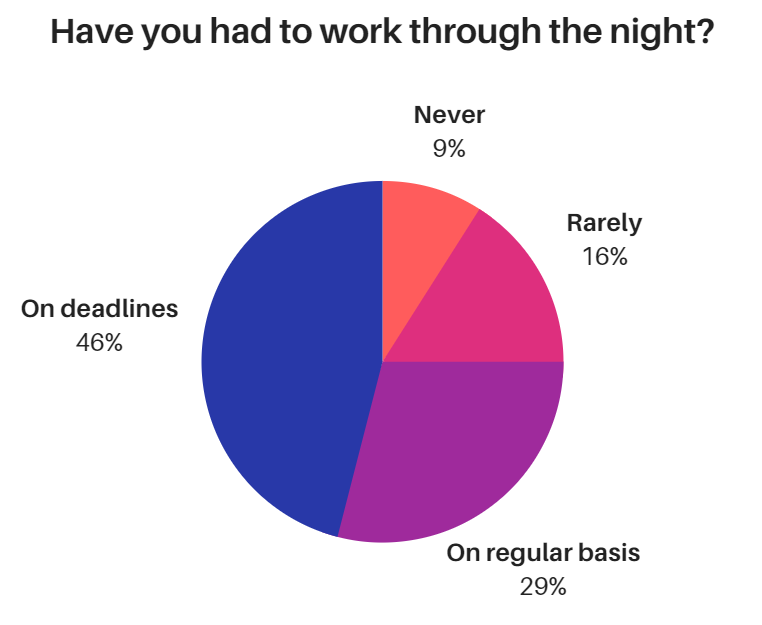

The survey also highlights a widely accepted culture of excessive working hours, a growing debt problem, and fears that education is not preparing students for practice.

We need to realize that the practical pressures students face are evidence of deep-seated cultural factors that need to be challenged, and it is important to speak more about the subject.

Chris Pretch from Penda—an emergent architecture firm with an innovative vision—opened a conversation about the topic of architectural education on his Instagram, in the hashtag #letstalkarch: [2]

Question in @chrisprecht_penda . He creates really interesting conversations around architecture and design.

Chris' comment about architectural education said:

“Although I loved it while I was studying, in retrospect i think my universities specialized too much on the design part. Architecture is not art. And architecture is not poetic.

Architecture is a business and we are entrepreneurs. I think one part of our job description is to seek out a problem and find a solution in a creative and unique way. The time of the master, the artsy architect who design for beauties sake, is dropping. Architects need to be hands-on involved with the problems of our time. And see them as opportunities to make a change. That’s a way our profession can stay relevant.”

This was an opportunity to read the thoughts of people all around the world, and it is surprising how a great percentage of the user comments said they don't think architectural education prepares you for the future.

Reading thoroughly there are problematic areas that are mentioned repetitively:

Lack of business knowledge:

While we're educating, nobody talks about the business life. I can relate it in a sense to the idea of the designer in a central role, lacking the context of how it serves the industry and relates to society and it's economy.

Pretch mentions how he missed these business and strategic courses as a student and suggests it would be helpful to include courses of how to set up an office, how to structure a team and methods to keep a healthy team spirit.

To build a career as an architect, you will probably need to speak about someone’s business and organizational goals. You’re going to have to learn how to do goal-driven work. Architecture is not about expressing yourself.

You are going to have to show your work and convince the client of how it will achieve those initial goals. You have to learn to communicate your work in a way that the people who will hire you understand.

Is it a project for a business? Is it about personal needs? Speak in peoples' language instead of strange words only architects use (there's even a list).

Compilation based on 150 Weird Words That Only Architects Use. (2015)

The truth is, architecture does not sell itself.

Perhaps the dynamic with the professor could be approached in a way that relates more to real business because the teacher in a way becomes your client.

That way it could be more objective. It's definitely not about «doing what the professor wants», which can lead to the very bad practice of just «doing what the client wants», when it's not about what anybody wants but instead of what is best for the project and how you as a professional present that.

Disorientation and overwork:

Perhaps why most of us felt that we didn't know what we were doing at the beginning of our career was precisely because frequently, academia doesn't explain what we are doing and why. Of course, teachers give general instructions but I'm speaking of facilitating the student with a bigger picture of their learning path.

For example, a friend who studied at another university told me that the first exercise they assigned her in architecture school was to make a model of a staircase. Okay, but why? Do you (or a whole class) really need to make a model to learn what stair runs and rises are?

And of course you have no idea of what to do, so you probably pull an all-nighter part-time working, part-time doubting your existence.

We take pride in our unhumanly effort and constant all-nighters that other people don't understand., and sometimes even continue working that way. Because it's how you do it, right?

AJ Student Survey 2016.

One time I was working on a project and my little brother was with some friends, and one of them said she wanted to be an architect. His immediate response was to say, in a spooky manner, «Oh no, you shouldn't. She never sleeps.», pointing at me, who in fact, was there with the face of a dead person to prove his point.

In hindsight, behind a lot of those constant all-nighters are unfocused work and poorly distributed workload. There. I said it.

If you are not clear of why you are doing things, and define a clear design approach with your professor (again, here the business skills are very much missed) you have to be doing and redoing things constantly. And that is a waste of time.

Besides, most of the all nighter time isn't quality work or effort. You can't be as productive if you are that tired and it is an unsustainable rhythm.

During all of architecture school I pulled all-nighters almost every single time there was a project deadline (or I remember it that way), and then I discovered that you work so much better when there is an execution plan you actually follow, design decisions are clear from the beginning so you can focus on developing technical details, and you sleep properly (this one was the biggest shift for me).

And retaking the staircase model example, I'm not saying that it's a terrible idea, it's just important to acknowledge architecture is a complex practice, and there is a lot to learn so there could be more fruitful exercises.

Instead of learning by trial and error in design critiques with professors, it would be better to learn methods for design, and learn from the teacher's experience about what things usually work in real projects, what things don't usually work (and why they don't), so you can complement with what you learn by yourself in a smarter and more effective way.

A negative pedagogy:

On the bright side, you definitely develop a thicker skin in architecture school. But it doesn't mean it's right. After giving it much thought, what bothers me the most in this area is that destructive critiques are felt to be a part of the pedagogical process of design education.

This way of teaching can undermine creativity and accentuate a negative thing: your fear of making mistakes, suffocating possibilities for the emergence of experimental practices.

I've seen a lot of mean cases and heard comments like: «if you put the model upside down it's better», or «this is the ugliest thing I've seen in my life», when objectively it can't be the ugliest thing anybody has seen in their life. Come on, there are really ugly things out there. Seriously.

Of course, it's important to be able to handle criticism and learn to not take it personally, but it doesn't mean we have to normalize being unkind to people. Feedback should be constructive and objective according to the goals of the project.

You want to encourage, not discourage, a person's development and commitment. Inspire people to do their best work and cultivate love for what they do. I believe it is one of the noblest pursues of teaching.

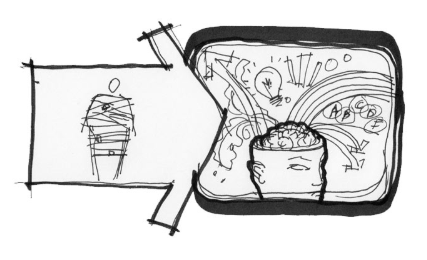

Illustration by Edson Cabalfin. (2018)

A narrow focus:

Architecture school, like many design professions, are a result of a collaborative effort, so a stronger convergence with other professions, from theory to practice, would benefit the experience of learning.

The reality is far away from one architect being the creative genius and instead there is a complex structure and a big number of stakeholders involved in each project, which you must learn how to navigate and bring into a harmonious and effective relationship.

The good news is that there is a growing interest in the world of design to combine ideas from different disciplines. For example, in a series of conferences in the Design Does Forum held this year in Barcelona, speakers suggested designers should be multidisciplinary and study subjects like philosophy, anthropology and economics.

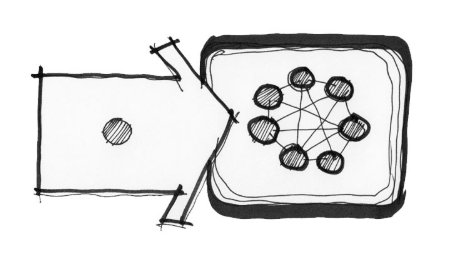

From architecture as isolated profession

To architecture as collaboration across disciplines and networks.

From architecture as singular and specialized profession

To architecture as diverse, multifaceted and multi-disciplinary.

A manifesto for architecture education in the 21st century. (2018) [3]

It's worth noting that curricular structures have hardly changed in recent decades, despite the major transformations that have taken place with the growth of globalization, new technologies, and information culture.

The value system embodied in architecture education and the profession needs to be recalibrated to meet the challenges of the future, advocating for architecture that is inclusive, humane, sustainable, innovative and creative.

References

(1) Waite, R., Braidwood, E. (1986) Mental health problems exposed by AJ Student Survey 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2018 from:

https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/mental-health-problems-exposed-by-aj-student-survey-2016/10009173.article

(2) Pretch, C. Post of February 5 2018. Instagram: @chrisprecht_penda.

(3) Cabalfin, E (2018). A manifesto for architecture education in the 21st century. Retrieved August 5, 2018 from:

http://bluprint.onemega.com/architecture-education-cabalfin/